Mastering Complexity

with the Futurist Toolkit

InnovationLabs Newsletter for July 2023

This rather long newsletter is an excerpt from our forthcoming book, “Hello, Future: The Next Ten Years,” a work in progress that will hopefully be done later this autumn. Entirely against my own advice to the contrary, the book seeks to sort out the tumultuous decade ahead and figure out what’s likely to happen. This excerpt describes the tools I am using to do

so.

Hindsight or Foresight?

Complexity Is Our Nemesis

Hindsight exposes good and bad strategies, but it’s foresight that matters. But long before the final results are revealed through the course of time there are inevitably long periods of uncertainty and speculation, sleepless nights of wonder, discussion, and worry about the mounting toll of unknowns. To talk of strategy, then, is to talk of potentials and risks, victories and failures, in war, in business, in games, and in life. And to work at strategy design is to engage with insight,

guesswork, intuition, and calculation, against a background of those same high stakes risks and rewards. Consequently, choosing the correct strategies, figuring out the nuances of their implementation, and putting them into action is rarely a simple matter. So, we will ask, what should our strategy be for coming up with our strategy? This is where the Futurist Toolkit can be so very helpful, for complexity is our nemesis, and tools which may help us cope with it are entirely welcomed.

Let us take the macro perspective and look for answers to the hot burning question, “What will happen to civilization if we keep doing things the way we’re doing them now…?”

We’re very well aware that things aren’t going so well, and that we need to change course. But the changes we need seem to be dragging along much too slowly. As a result, we’re living in a multi-shock environment, buffeted this way and that by the gales of the past. Hence, another way to ask our question is to consider, “How should we cope with all the shocks? And what should we do to treat the multiple traumas they’re

causing?”

The Futurist Toolkit described here provides a means for doing so. It replaces hindsight with foresight, and guesswork with strategy, and so helps us to cope with the many shocks as it also sets us up to face the future.

Which shocks am I talking about? Well … there’s eco-shock, the extensive damage being done to the natural world, which includes all too obviously worsening climate change, econo-shock, the shift to a new, post-industrial economic model, demographic shock, the rapid inversion from a population boom to bust, urban shock, the rapid growth of cities and the emptying of the countryside, and finally future shock, the psychological trauma caused by the

disruption to past norms of society, and by its accelerating change. The modern world is simultaneously subjecting us to all if these, putting us into a kind of a perma-shock environment. And as a consequence we are indeed suffering. Society, civilization, sanity, and the future all seem to be quite at risk, as many observers have poignantly reminded us. Here are three of them:

“Civilization is in a race between education and catastrophe.” ― H. G. Wells, 1921 (The Outline of History, Vol. 2, ch. 41, sec. 4)

“Humanity is now clearly faced with the choice of Utopia or Oblivion.” – Buckminster Fuller, 1969 (p. 202)

“By violently expanding the scope of change, and, most crucially, by accelerating its pace, we have broken irretrievably with the past. We have set the stage for a completely new society and we are now racing toward it.” – Alvin Toffler, 1970 (p. 16)

Toffler, of course, is the one who coined the term “future shock” to describe our shocked psychological condition. When such a shock occurs, here’s what happens:

“The initial symptom of shock is feeling a surge of adrenalin. You may feel jittery or physically sick, like you're going to vomit or have diarrhea. Your mind will likely feel very foggy, or like you can't think straight. You may feel out of body. Your chest may feel tight. You may feel a disconnection from what's happening, like you're watching a

movie of events unfolding rather than actually being there. You may feel intense anger and want to scream or yell. You may feel like you want to run. These symptoms are all part of the body's acute fight, flight, or freeze response. Your body prepares you for fast, thoughtless action. For example, blood rushes to the muscles in your limbs ready for you to spring into activity; we tend to hyperventilate as well, which leads to the cognitive symptoms of feeling spacey and

foggy.”

(https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/in-practice/201803/what-is-psychological-shock-and-5-tips-coping)

Shock is thus a set of self-protective reactions that the mind-body system adopts automatically. And across all of modern society it’s clear that a people everywhere are experiencing many of these symptoms more frequently and more intensely, as a consequence of the repetitive shocks they’re experiencing. In particular, extreme anger, anxiety, and blame are now chronic

manifestations. In many places mass shootings are now a regular occurrence (especially in the US), the political divide is worsening worldwide, and there is a gradual breakdown in social cohesion. All of this is fully reinforced and indeed amplified by polarizing news media and even more polarizing social media.

But by way of a reality check, the doubter or devil’s advocate might want to suggest that what we’re experiencing should actually be considered somewhat normal. Of course there’s going to be change, so perhaps all this anxiety about shocks is overwrought. What if everything is actually going along OK? What if the alarmists are merely a crowd crying wolf when there is no wolf, or Chicken Littles panicked about the falling skies that are actually

staying up there, just where they’ve always been? Or, stated differently, is all this shock just today’s version of a timeless story of change?

The best way to answer that question is to compile actual evidence in order to discover what it may be able to tell us. (The alternative would be to make guesses, assumptions, and assertions based on our biases, a simpler and less informative but far more common choice.)

So where shall we look for evidence, and how would we model it? We have a robust set of tools available to us to help us better understand the present and therefore anticipate the future, and then to better organize the influence we may have in shaping what’s to come. These tools constitute a process for learning, a learning system in fact. In this chapter we will examine them, and then in Part 3 we’ll follow the learning pathway as described here,

compile the evidence, and see what it tells us.

The learning process begins with data.

Data: Tracking Events and Trends

A lot is happening, and as limitless curiosity seems to be inherent in human nature as a fundamental aspect of our genetic programming, we want to know what’s going on all around us and far away, who did what, and why. So we pay attention, often intently.

Surround by and immersed in electronic media, we live within a continual tragi-comedy news and gossip theater. Filled with viral micro-trends, live updates on the bad news of the moment, and now endless waves of social media messaging, it is the nonstop dialog of a society that loves to talk to itself, about itself. It might not be wrong to call this an addiction, and it is so pervasive that it takes considerable effort to avoid getting sucked in.

Because so much of the news and messages are bad, the non-stop hashing and rehashing of the poly/perma crisis, some organizations have gone so far as to implement so-called Social Media War Rooms where they track numerous media outlets on a minute-by-minute basis so they won’t be caught by surprise when bad news or negative messaging hits. These often look like NASA control rooms or telecom network operations centers, rows or desks facing large screen displays on which the

news/twitter/tiktok tsunami is displayed. Here is a photo of a Facebook version:

But as futurists, our interest in the news is primarily because we wish to understand where this all leads, to grasp the longer cycles of change, monthly, annual, and decade-long transitions and transformations. Consequently, we follow the flow of events to develop maps, models, timelines, and forecasts which then constitute our guide to the unfolding future.

We also engage with sources other than the news and Twitter, scholarly and academic publications and web sites, trade shows and conferences, and even books. Conferences and exhibitions are valuable because exhibitors intend to portray their goods and capabilities in the very best light possible, so they depict idealized future products and services that give

insight into what they think is possible. While those visions may never be realized as depicted, it’s often fascinating to see what people think will be possible and desirable for the future.

We also engage with sources other than the news and Twitter, scholarly and academic publications and web sites, trade shows and conferences, and even books. Conferences and exhibitions are valuable because exhibitors intend to portray their goods and capabilities in the very best light possible, so they depict idealized future products and services that give

insight into what they think is possible. While those visions may never be realized as depicted, it’s often fascinating to see what people think will be possible and desirable for the future.

Narita Airport, Tokyo: Human & robot interacting

And of course this game is different now, changed fundamentally by the arrival of AI. To test this, on January 8, 2023 I asked ChatGPT, “What will happen in 2050?” This is what came it back with a few moments later:

It is difficult to predict with certainty what will happen in 2050, as it is more than 30 years in the future and many factors can influence the course of events. However, there are some trends and developments that are likely to continue or accelerate over the next few decades. One trend that is likely to continue is the increasing impact of climate change, which is expected to result in more extreme weather events, sea level rise, and other impacts on the environment and human societies. Another trend that is likely to continue is the rapid pace of technological development, which is expected to bring significant changes in the way we live and work. It is also possible that other unexpected events or developments could occur in the future that could significantly impact the world in 2050. For example, advances in fields such as biotechnology, artificial intelligence, or energy production could have major impacts on society and the global economy.

It was a surprise that the AI got the math wrong (as of Jan 8, 2023, 2050 was 27 years in the future, not “more than 30”), but the rest of its suggestion seems quite plausible. With the arrival of widely accessible and increasingly capable AI tools, we have now the capacity to monitor and track a vastly wider span of content, and to do so nearly in real time. As of this writing,

futurist-oriented AI tools have not yet been widely disseminated, but it’s just a matter of time until they become common. By the time you read this you may well have your own personal AI engaged in nonstop monitoring and modeling just for you.

Given such a robust and possibly overwhelming set of data about what’s happening, what can we do with it? (And what can the AI do with it?) We need to transform it into information.

Information and Knowledge: Mapping the Future

All the data is raw material that will enable us enter a new world of possibility as we and AI will study it to develop a set of highly detailed and very useful maps, models, and forecasts. These will help us to grasp key patterns, and thereby provide insight into possible and probable futures. (Please notice that we are still avoiding the trap of expecting a singular future to arrive; the

conversation remains focused on possibilities, and does not aspire to make point predictions for specific future states.)

Past-to-Future Timelines, which may go back 20 or even 50 years and 20 to 50 years in the future, are very useful for tracking key trends and thinking about how past events influence future ones. A deep knowledge of the past relies on history to tell us the stories not only of great events, but of the unfolding patterns of change that have occurred across centuries and even thousands of years. And we well remember the warning of philosopher Georges Santayana, “Those who forget history are

doomed to repeat it.”

Mapping the past enables us to benefit from the accuracy of hindsight, and to trace the acceleration of events. We can then extrapolate trends forward, not necessarily to peg the future exactly right, but to see the past-to-present-to-future continuity, and reflect on both the continuous flows of the historical timeline, and the shocks which may disrupt it.

Product and Technology Roadmaps are very commonly used in business, particularly in technology firms, to plan out product development investments in conjunction with competitive market assessments.

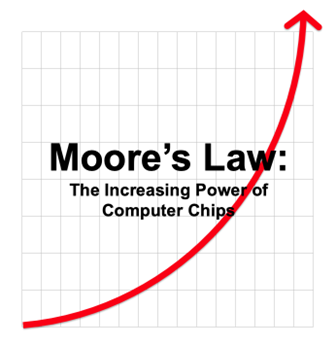

The best roadmaps often reflect or apply underlying models of technological change, such as Moore’s Law, Moore’s Second Law, Metcalfe’s Law, Joy’s Law, and Tuchman's Law.

- Moore’s Law, formulated by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, anticipates the rate of improvement in computer chips. Moore realized in 1965 that chip capacity was doubling every 18 – 24 months, which has had profound implications. It describes, in effect, how technology enables the digitalization and thus the transformation of the entire economy.

- Moore’s Second Law, partially tongue in cheek, observed that the cost of each new generation of computer chip factory (called a Fab) also doubles as the technology becomes ever more sophisticated, still more microscopic.

- Another computer scientist, John Metcalfe observed that the value of a network increases as a square of the number of connected users. This yields an exponential valuation curve for growing networks. All economic phenomena that rely on networks reflect this, hence the massive valuation of companies like Facebook and Twitter, which are essentially platforms for enormous networks.

- Joy’s Law, named for technology entrepreneur William Joy, notes that “the smartest people work for someone else,” which explains why open networks and crowd sourcing for solutions can be so effective.

- Historian Barbara Tuchman's Law states that, “The fact of being reported multiplies the apparent extent of any deplorable development by five- to tenfold.” In other words, people exaggerate. She further notes that, “History is made by the documents that survive, and these lean heavily on crisis and calamity, crime and misbehavior,” which leads to what she calls “negative overload,” that when hammered away constantly as we now experience, often becomes future shock. (Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, p. xviii)

Again, the point of all these laws is that they describe significant patterns in technology, the economy, and society. They therefore help to explain what’s happening, what has happened, and what may yet occur.

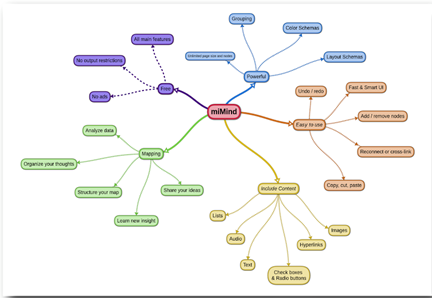

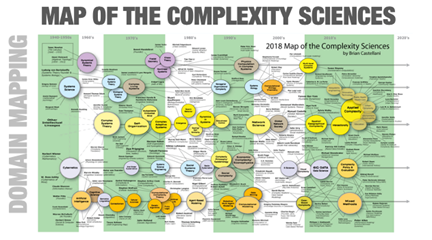

- MindMaps help us visualize complex networks of concepts, institutions, and objects.

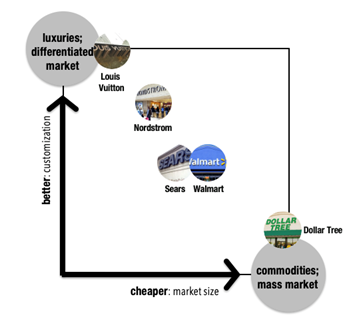

- Market Maps show key competitive dynamics and help to visualize, and thus identify, strategic options.

- Relationship Mapping shows how various entities in a given domain relate to one another, and can also be very helpful in seeing patterns of change. Social Network Mapping, for example, shows how various people in a system (like a company) are connected in various ways, and help to explain how things work and to diagnose organizational dysfunctions.

You have certainly noticed that each of these tools draws in a broad sweep of content and seeks to make it useful and accessible. Some do so by portraying the span from past to present to future in a visual way, others by showing how entities or ideas are connected. This is indeed how we recognize patterns, not as columns of numbers or as interminable lists, but as flows that draw from history to portray the future. A good graph can make crystal clear what a table of figures may entirely obscure.

Moore’s Law, for example, looks like this, helping to grasp that the computer of 2020 has orders of magnitude more capability than that of 1995. This has immense power to explain what’s been happening.

But even the maps and graphs don’t convey the full scope of change, so to complement the visual approach it’s often useful to nurture the stories that these maps are wanting to tell us. Narratives are particularly helpful because the timeless structure of storytelling is a universally-understood means of conveying complexity. Throughout our childhoods we are immersed in stories and storytelling, and the broad appeal of written fiction, TV, and cinema reflect the intense human

affinity for the power of narrative to entertain us, to educate us, and this to shape our views. We use stories to foster imagination, to explain our sufferings, to inform our awarenesses, to educate our choices. Thinking about morality, we craft fairy tales; thinking about fate, we compose myths; considering our life challenges and choices we write novels; imagining the future we create science fiction, which helps us see utopian (such as Star Trek), and dystopian (such as Star Wars)

possibilities. All these genres are variations on timeless themes that help us to understand how the future may unfold, the qualities and characteristics of various possible futures, and even key events, forces, and factors that may bring any particular future into being. Universal human experience is adorned in the compelling imagery of war and peace, greed and power, success and failure, love and sacrifice, childhood and old age, life and death.

And so what have we done? From raw data we have crafted a map and stories to explain it, which gives it depth, nuance, and understandability, which translate the universal and cosmic into the intimate and personal. And how, then, may we make the best use of them?

Understanding the Emerging Flow of History: Connection, Patterns, and Structures

It’s important to remember that tempting as it may be, we will resist trying to predict specific future events and states. Predictions, as we know, are nearly always wrong. Instead, we use our maps and models of the future not as the end point of our learning process, but to look for patterns that may reveal still more about possible futures. Once we see the patterns then our situation

will become much clearer, as we can then prepare realistic risk assessments, our options become much better defined, and therefore we can frame our choices effectively. This understanding is thus the basis of effective thinking about strategy, and effective action-taking to implement strategy.

We also understand that whatever choices we make will have to match the emerging flow of history, and as unpredictable is the watchword, we’ll maintain a close watch on unfolding events and trends to assure that our models and choices remain valid. As part of this thinking process we will therefore seek to identify key leading indicators that will tell us when things are changing and not changing. The search for indicators thus gives the social media war rooms another key role, monitoring

strategic indicators in addition to keeping a close eye on the viral flow of public dialog.

And when we discover that the arc of change has shifted, that things have turned and therefore that our choices may no longer be optimal, we’ll have to be prepared to pivot. But pivot to what? Since we chose our strategies based on expectations that have been shaped by maps and models, we’re in good position to recalibrate because we have established what is in effect a portfolio of strategic options, and then we chose a specific set of options based on the logic of plausibility and

advantage at the time. When that logic changes, we adjust accordingly.

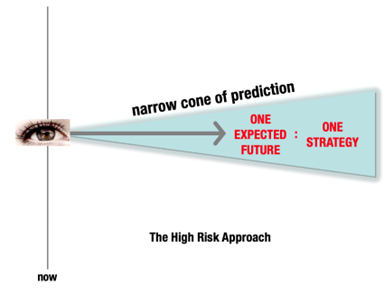

Thus, the overall perspective is this: We have shifted our thinking beyond an attitude of choosing strategies based on a narrowly configured, preferred future, the ones we thought most agreeable, plausible, and advantageous, to identifying patterns of change in key driving forces, and then creating a portfolio of options accordingly.

To discover the connections, patterns, and structures that are bringing the future into being we will ask probing questions, like these:

- How are various driving forces connected to one another?

- How, then, do changes in one result in changes in others?

- What are the deep structures that are driving these forces forward?

- How will these structures respond when they are put under stress by the many strong pressures acting upon them?

These are certainly fascinating questions, but there is a risk that they are so vast and open-ended as to lead us into a looping morass. We therefore need to organize our queries. We need a method or process to give structure to our thinking, to make it productive and effective. And for this, happily, we do indeed have a quite useful tool.

Possibility Axes

It is very useful to test a wide variety of possibilities in discreet thought experiments. Deep insight can come by defining a set of key themes, variables, or driving forces and considering the possible and probable future states of each, and then by combining various of these themes and considering them together.

With regard to the economy, for example, it’s necessary to look at the possibility of future economic boom as well as a future economic bust.

We’re not trying to predict which will become the reality, boom or bust, but rather we’re exploring what would happen in each case … especially so since both are entirely plausible. By setting up the inquiry in this way we automatically examine a diverse set of possibilities.

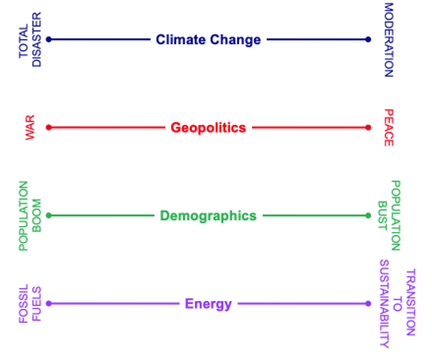

Many comparably important topics are important from the macro perspective of the broader world, as well as from the specific perspective of our organization or institution, and indeed I’ve already mentioned a few that I believe are decisive, including climate, geopolitics, demographics, and energy. All of these are critical to our present condition and to the future, and they will certainly be in the center of the action no matter what ends up actually occurring.

For each theme or topic we identify, we then define the extreme poles of our possibility axes:

By doing this and resisting the temptation to expect one pole or the other to become the future, we have already set up a rich learning situation for ourselves. We are seeing the world as a matter of possibilities rather than predictions.

Future Worlds

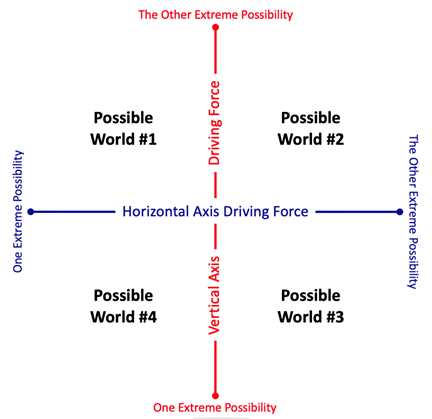

We can gain further insight when we then pair these driving forces, thus shifting from two possibilities to four. This introduces a much deeper level of complexity into our thinking because now we explore how the two extreme possibilities of two key driving forces might interact.

We have created four possible future worlds. Each, as we are reminded by the oft-mentioned lesson from the Chinese language, composed of both risks and opportunities.

It is true that by selecting two forces we have vastly simplified the enormity of the future, but we have done so without trying to identify any one specific future. It’s been an open-ended thought experiment oriented around possibilities and plausibilities, genuine learning.

The commonly used name for this thought experiment is “scenario planning,” and as you see, we have by now moved far beyond narrow expectations for the future and helped ourselves to recognize that rather than trying to predict exactly what will happen, we have now become aware of many possible futures.

Countless times we have observed working groups thinking through the 2x2 matrix of possibilities and discovering new insights and connections which surprised them, enlightened them.

But of course the future will not be made by just two driving forces, so when we engage in a planning project we may create a dozen or more of these 2 x 2 matrix combinations, which will enable us to consider how many different driving forces may influence one another. We begin to see patterns, and to understand how various possible futures could emerge.

This is now, in effect, a systematic effort of thought experimentation, and it can achieve many desirable outcomes. Perhaps most significant among them is that this is an explicit learning activity that occurs as we think through the implications and possibilities of significant interacting forces because we aren’t making decisions, we’re exploring what might happen or could happen, what we prefer and what we fear.

There is no intellectual substitute for sorting out a wide variety of future conditions, especially when we then recognize that many of these futures, favorable and unfavorable, are plausible. Again, we have shifted our mental approach away from thinking we know what’s going to happen in big picture situations (because we generally don’t even when we think we do), to recognizing a wide range of future states that really could come to pass (which generally is the case).

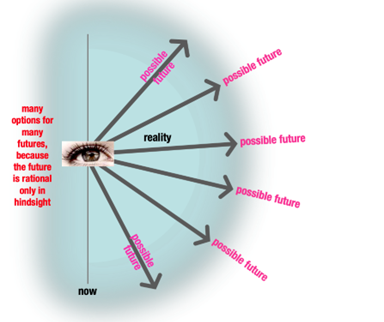

Hence, we have develop a deep understanding of the future by shifting our expectation from the highly deceptive and high risk narrow cone of prediction …

… to seeing a much broader cone appreciating that the future is wide open and full of nearly limitless possibilities. Accordingly, we make a significant mental shift; we see the future in an entirely different way.

But now what shall we do, given what may in fact be a nearly overwhelming range of possibilities?

Wisdom: Designing and Implementing Strategy

We have by now progressed from data collection … to mapping … to understanding the patterns. Each step has yielded significant value toward our ultimate goal, which is making the best choices.

Making strategic choice is the task of leaders, and we certainly do wish that our leaders are able to choose wisely. Indeed, this is the whole point of leadership, wisely defining strategies and making really good choices on behalf of us all.

Hence, I am here describing how to design effective strategy in a highly complex environment.

A Portfolio of Strategic Options

Now we see how uncertain the future really is, so we can no longer be satisfied to create strategy that fits only our expected (or preferred) future. Indeed, we have by now defined many possible futures, and we must therefore consider the strategic risks, possibilities, and options associated with each of them. And since these possible futures are quite different from one another, the relevant strategies may well be

vastly different as well. Hence, as I mentioned above, what we’re creating through this learning process is actually a portfolio of strategic options, from which we may then choose to adopt as a wide variety of future conditions will require. This approach will enable us to adapt to whichever futures actually do arrive.

Working this way provides vastly superior strategic positioning, and is far more likely to enable our organizations to survive and thrive amid the vast uncertainties of accelerating change. It’s much better than picking a single target and going for it, because if the target shifts, disappears, or fails to emerge as expected….

In other words, we are now much better prepared when things don’t go quite as hoped or expected.

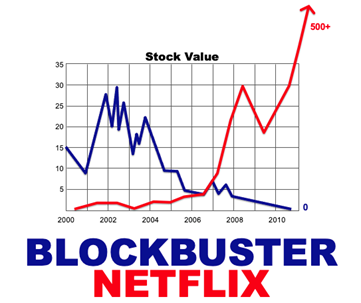

Here is an interesting graph showing two companies with diverging destinies, followed by a simple story that explains the graph.

Blockbuster & Netflix

Blockbuster, the video cassette rental company, had by year 2004 come to absolutely dominate the enormous American video rental market. They had 9000 stores, 60,000 employees, and annual revenue of $5.9 billion. Thousands of customers came into their stores each day, browsed through around 60,000 titles, and walked out with the movies they would watch that night. Blockbuster was the undisputed king of this market. (https://www.businessinsider.com/rise-and-fall-of-blockbuster#despite-the-rise-of-netflix-and-redbox-blockbuster-was-at-its-peak-in-2004-10)

A startup company had also by then entered the video rental business, but they sent movies on CDs via the US mail to their customers.

These were two completely different business models, Blockbuster transaction-based, a fee paid for each cassette or CD, and Netflix subscription based, a fixed fee per month for as many movies as you wanted to watch.

The founders of Netflix thought that the two business models could be combined, and they suggested putting them together into one company. When they mentioned this to the leaders of Blockbuster, they were met with derisive laughter. Why, wondered Blockbuster executives, would the king even consider buying this silly little startup company?

You know what happened, and the graph says it clearly. Soon Blockbuster went bankrupt and disappeared, while Netflix grew into a company that is now worth 3,860 times the amount they asked for to sell themselves to Blockbuster ($193 billion as of July 2023). Any CEO who could achieve a 3860x gain would often be hailed as a genius (and Reed Hastings of Netflix sometimes

is), but hindsight condemns those who walked away from that deal to ridicule.

When we look at this story through the lens of our future learning model, it’s easy to see that the Blockbuster leaders assumed that their retail store kingdom was impregnable, that their competitive advantage was durable, that the upstart posed no threat. They assumed, that is, that things would remain as they then were, indefinitely. They were quite wrong. They apparently did not conceive of how advancing technology would change their industry (streaming came soon after this story), and

they did not conceive that a different, and much more convenient way to rent movies might be appealing than retail stores. Given the opportunity to create a strategic portfolio for the future, they declined to do so. Ridicule indeed; $193 billion or zero.

The business world is bursting with stories like this, I mean literally full of them. The business press thrives on these failures, as they sell and sell and sell, and hence this is one of the universal themes, the once-great company brought down by its inability to adapt, by the short-sightedness of leaders who did not grasp the future.

But leaders know as well that it is inherent in the nature of a competitive marketplace that innovators attempt to gain competitive advantage by doing things differently and better, by leveraging new technologies, and by responding to changing customer expectations. For reasons now very well understood, older, established firms have a terrible time doing what many upstarts do instinctively well. (If they have better models of how change occurs, they would be much better at it. Hence the astute

comment from Netflix CEO Reed Hastings, “If we get lazy or slow, we’ll get run over, just like anybody else.”)

All the discussion here about accelerating change and its accompanying risks and opportunities confirms this, as we observe the emergence of breakthrough strategies and the companies and nations that define and exploit them, or fail to do so. What strategies doomed the ancient empires or modern failed states, or enabled the world’s superpowers to emerge? How dd Napoleon conquer Europe, and how did the European monarchies win their kingdoms back? What made IBM a once-great company, but one

that has faded nearly into irrelevance? Why did Sears collapse while Walmart, Alibaba, and Amazon thrived? How and why did Nokia succumb to Apple?

Each of these can be seen as a graph, like the Blockbuster/Netflix stock chart, with a tantalizing story that explains it. But stock charts are only useful in hindsight…! We have to switch over to foresight …

Change Takes Its Toll

Today’s world of accelerating change and increasing complexity creates situations of great challenge, and we see strategies that were not so long ago accepted as given truths are suddenly hollow, tired, and inept. Changes takes its toll.

The world of geopolitics is no different, as competition between nations is likewise affected by factors including innovation, public expectations, and also by nature.

For example…

Two technical innovations among many have been particularly significant factors in the rapid expansion of the Chinese economy in recent decades. The internet facilitates high quality interaction throughout global supply chains, which makes it possible for the Chinese manufacture products for the entire world because their customers no longer have to travel to China to manage design and production. Real time interaction facilitates the production process. And second, the shipping container makes

it efficient to deliver the huge quantities of goods that the Chinese produce from Chinese ports to the world’s consumers.

And the role of popular expectations? Consider the impact of revolutions throughout the last three centuries of history. The American and French revolutions both arose from the popular will, and both completely changed the geopolitical situation. They were followed by nearly a century of uninterrupted revolutions across Europe, all of which reflected popular aspirations for democracy or independence. The Arab Spring movement that began in 2011 was essentially no different, and so when more than

a million people gathered in central Cairo’s Tahrir Square to demand a change in government and the end of authoritarian repression they were expressing the same aspiration.

Technological change, market change, social and political change are constantly reverberating off of one another. When these waves of change start to synchronize they begin to amplify, and when they do revolutions often result: big change is often the consequence of such confluence. Which brings me back to the confluence of shocks I mentioned above, and the conjecture that this may well be a

time of monumental change, of transformation or revolution, because so much seems to be changing at once – ecology, climate, demographics, economy, and technology ….

Imperatives

In the face of all this change, and having developed a portfolio of possibly useful strategies, we are rudely confronted with the difficult problem of which we should implement? We shouldn’t just sit and wait for change to envelope us (à la Blockbuster, for example), so what do we do instead of just waiting around for the future to crush our hopes?

The design and implementation of strategy in a highly complex environment is all about taking action.So given a set of conceivable futures that evoke a quite broad range of possibilities, and given a set of possible strategies to address these conceivable futures, what must our organization do to succeed across all of them (or most of them)? The things we have to do are called the “imperatives.”

That is, having gained insight into possible futures, we can now put in place capabilities that will enable us to meet the future well. These are the actions we will take today that will lead us toward preferred futures amidst the broader uncertainties of change. Experience has shown that imperatives generally come in two varieties.

The first are related to learning: knowledge, capabilities, and processes.

- What knowledge that we do not presently have will we need to succeed in the future?

- What capabilities that we do not presently have will we need to succeed in the future?

- What processes that we do not presently have will we need to succeed in the future?

For instance, as we have just now (and suddenly) moved into an era when AI is a major factor throughout the business world, organizational leaders must understand what this may mean; that is, they require knowledge. And if they intend to apply AI technologies (which they will), then they will need trained staff, that is, capabilities (i.e., knowledge translated in action).

(SIDEBAR: Note that when a new and necessary capability such as AI emerges, there is often a shortage of people with the requisite expertise, and so an arms race arises to find them. Hence, now that everyone is attuned to the importance of AI, skilled people are in short supply. How significant it is for organizations to recognize that this is coming ahead of time and built their AI teams a bit ahead of the need? Thus the value of strategic foresight…)

Having the new capability in place then creates another requirement, as it’s necessary to define how the capability will be applied, deployed, and exploited to create strategic success and therefore competitive advantage; or more simply, what do we do with the new thing, how do we use it?

Since the beginning of industrialism we have seen countless waves of new technologies that presented exactly this sort of problem for organizations and nations, and then the same is occurring again with the rapid advance of the digital era. Companies had to learn about computers in the 1950s and 60s, microchips in the 1970s, master the internet and develop a web presence in the 1990s, figure out globalization and e-commerce in the 2000s, supply chain automation, and then social media, and then

mobile, data and analytics, fintech, and then cyber security, and now AI and predictive analytics, robotics, AR and VR, and soon, perhaps, the metaverse and quantum computing as well …

Each advance brings change to the competitive landscape, and each therefore requires knowledge, capabilities, and processes to make use of them.

Looking forward, it’s obvious that all these technologies will continue to morph into still more advanced forms and applications – Moore’s Law predicts this – and they will likely be even more disruptive, and we will have to learn how to use them.

Hence, the pattern is clear: when a new technology moves from leading edge of early experimentation into mainstream usage, a new imperative is suddenly born. But it takes time to understand what it may mean (how it applies to us), and then to identify the knowledge, capability, and process targets. It then becomes necessary to hire and train staff, or engage consultants, to begin to put in place the operational elements to take advantage of the possibilities, while also defending against

competitors that will attempt to deploy the same technology to gain competitive advantage. All in all, it is a morass of uncertainties, as expressed here by economist Brian Arthur from the perspective of the high-tech entrepreneur. Arthur is describing what we refers to as “combinatorial business,” one that integrates separate technological capabilities into a single offering. As this is the archetypical business situation of the 2st century, the problem as defined here is the

universal one:

“For the entrepreneur in a start-up company, little is clear. He [or she, or they] often does not know who the competitors will be, how well the technology will work, or how it will be received. The environment that surrounds the launching of a new combinatorial business is not merely uncertain, it is unknown [and at the time, unknowable]. This means that the decision problems of the high-tech economy are not well-defined. As such, they have no optimal ‘solution.’ In this situation the challenge of management is not to rationally solve problems but to make sense of an undefined situation. Entrepreneurship in advanced technology is not merely a matter of decision making. It is a matter of imposing a cognitive order on situations that are repeatedly ill-defined.” – Brian Arthur, 2009 (The Nature of Technology, p. 208)

Organizations – whether start-ups or established firms – that anticipate these conditions are in much stronger positions than the laggards, and hence the logical argument in favor of scenario planning as tool for foresight, and the significance of correctly identifying the imperatives.

The second type of imperatives are the actions. As we’re not going to just sit around and wait for the world to change so we can get blasted by a world we can’t compete in, we have to take action in parallel with and supported by our learning. We intend to do stuff, to create change. What shall we do?

In Arthur’s example, the entrepreneur has already decided to establish the business; the monumental task which then arises is to determine a workable business model. And for this, both the entrepreneur and the established firm (desperately) need a roadmap.

Strategic Roadmapping

What must we accomplish to translate our knowledge of the future into action initiatives that will enable us to meet the future’s likely requirements? Or more simply, what we have to do to get from where we are to where we want to be, hence the roadmap metaphor.

What we’re talking about here is the design and implementation of strategy, a subject of deep and enduring interest throughout all of history, just as remains so today.

History tells us that good and great strategies, well executed, make for success and victory, while poor strategies often lead to failure, defeat, and sometimes collapse. In business, like Blockbuster. In geopolitics, like the dozens of failed empires of the past.

This has always been a topic of fascination, and some of history’s greatest and most compelling literary works deal with strategy, triumph, and collapse in their many variations. Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Machiavelli’s The Prince all examine the same dynamic.

Since strategy takes as its very purpose the transformation of beliefs about the future into actions in the present, it is necessarily about anticipation, decision, risk, and ultimately about commitment to a path forward, all themes that we are exploring throughout this book.

Earlier I mentioned that hindsight exposes good and bad strategies (Blockbuster again…), but it’s foresight that matters when you’re creating strategy.

Possible strategic concepts, once conceived (even those that seem perfect), need to be articulated, refined, and tested. In most cases, people other than those with the original intuitive sparks also have to become convinced of a strategy's validity and effectiveness because their efforts will be required to implement it.

So clearly what's needed is some sort of an organized, systematic process to enable people to understand the strategic essence of their situation, and then to craft effective, compelling responses, winning strategies. As scenario planning is about understanding the situation, what follow is Strategic Action, through which we define and communicate the actions intended to prepare us for the future.

I say defining and communicating because it's not enough to have winning strategies if people don’t understand them, don’t agree with them, and can’t or won’t implement them. If people who need to implement don't understand the strategy, or don’t agree with it, then you may as well not have one at all. Hence, the process of how and what to communicate can be as important as the strategy itself.

It’s a plan of action, that defines the steps to get from wherever we are in the present to where we want to be in the future. But importantly, because it’s a map into an unknown (and per Brian Arthur, unknowable) territory, because the path defined by a strategy can be proven only over the course of its implementation, in its formulation stages it’s necessary to remain aware that what we really have is merely a forecast … that is based partially on evidence and

partially on hypotheses and expectations, concerning what we believe will work for the future. Consequently we must be prepared to adjust the map, and our course upon it, as events unfold.

Given all these factors, we can break down the elements of a Strategic Roadmap into five elements, as so nicely defined by our colleague Bryan Coffman:

The Strategic Goal Defined

The Strategic Pathway Defined

Changes to Systems and Structures Identified

Adoption Enabled

Transition to the New Systems and Structures Achieved

Defining the Strategic Goal: Push, Pull, and Hedge

The core of any strategy is its goal: What do we want our nation or our organization to achieve? A goal reflects the push of threats to survival, the pull of a desire to create a better situation for ourselves, and the need to hedge risks caused by burgeoning uncertainties. A strategy itself is thus understood to be the method by which we expect to attain the goal.

Since we’re using the metaphor of a map to guide this process, we see that to define a suitable goal (or goals) we have to understand the current terrain and where we are located in it, and also understand the other relevant players in our territory or marketspace. Common business tools like a SWOT analysis are good for this.

We also need to understand our current internal capabilities, the things we can do today, our skills.

In business terms, the goal may be a destination, such as a sales volume objective, market share, or profitability target. Once achieved, new goals will take their place. The goal may also be a performance measure that must be sustained indefinitely, such as “return on equity” or “number of defects” (i.e., six sigma). And the goal may also be understood as achieving a certain position in our sphere of influence, market or profession, or the policy influence we attain on a

larger system.

China, Russia, the EU, Japan, and the US all have clearly identifiable goals with respect to geopolitics, and they are not all aligned; some will achieved at the expense of others.

Most organizations and all nations will articulate compound goals consisting of many distinct but often interrelated elements.

Defining the Strategic Pathway

Having goals is one thing, but by what methods or mechanisms will the goals be achieved?

Such mechanisms are the path of logic that can be stated in a simple “IF, THEN” format: “If we do X, then the strategic goal Y will be achieved.” It expresses an intention and a belief about cause and effect, and the implementation steps taken along the pathway will tend to prove or disprove its validity.

To be complete, a strategic pathway needs to be articulated in three ways.

• First, there should be a diagram that shows cause and effect links.

• There should also be a story that describes the strategy in action, not simply as an explanation of the diagram, but as an illustration that enhances understanding, insight, and agreement, which expresses an action plan.

• Finally, the elements of the strategic pathway need to be quantified so that the whole chain of cause and effect can be tested. This may be done using a simple spreadsheet or a more complex financial model.

After we have defined the strategic roadmap in concept, we next need to understand its critical details so that it can be implemented effectively. For this we look at these essential elements:

Changes to Systems and Structures

Adoption of the New Strategy

The Transition from Old to New Systems and Structures

Understanding the Changes to Systems and Structures

Chances are the new strategy will require changes to the way our organization operates. What are the current structures, processes, behaviors and capabilities of the system that must be changed to enable the strategic pathway to be realized? What, in other words, do we have to now do differently?

Enabling Adoption

The process of adoption is all about perceptions, the politics of getting an organization to adopt the strategic pathway and all the changes it may entail. It’s about removing friction in the organization and creating an infectious spread of enthusiasm for the pathway so that everyone is aligned with it. What will be required help the current organization adopt the strategy? Who has to be convinced, and what will convince them?

The Transition to the New Systems and Structures

This transition is the set of projects and programs that have to be resourced, implemented, and put in place: the new system and its structures and processes, and the projects and programs must be implemented to support the transition to this new system.

These five elements constitute the roadmap to the future organizational state we wish to achieve, and thus it is the strategy. It is as a complete as it could be given the inevitable uncertainties, as it tells us where we are, where we intend to go, and what we believe must be done to get there.

Yet as we transition to implementation, we never forget that the changing external environment may present us with new requirements, and thus the likelihood that we will have to adjust the strategy going forward. Actually, it’s not so much a likelihood as it is an inevitably. The future is not a stable system in a stable context, it’s fluidly dynamic and constantly creating new conditions and challenges that we must be ready to recognize, evaluate, and respond to. Hence, as we move

forward along our roadmap we will discover that the actual road is not exactly as we envisioned it on our map, and so we necessarily adjust course to reflect emergent realities.

Indeed, from the perspective of hindsight it’s pretty easy to see that the strategies that failed, and the organizations that followed failed strategies, were the ones that kept to pre-defined strategic roadmaps that did not, in the eventuality, match the road. Like Thelma and Louise, off the cliff they drove…

Mastering Complexity

Scenario planning and strategic roadmapping require us to grapple with and eventually master complex issues. Or, in the tart words of the CEO of a major bank: “It’s a shitload more complicated than it’s ever been.” (Schumpeter, The Economist, May 6, 2023)

Mastering complexity requires that people from many different perspectives, and who have deep expertise in many technical, operational, and strategic areas, must work together to share their expertise and develop a shared understanding. Hence, scenario planning and strategic roadmapping generally work best as collaborative efforts. In this way they also become shared learning experiences which result not only in their tangible outputs, scenarios, strategies, imperatives, and action plans, but

just as importantly, the benefit of cohesiveness as teams develop a deep and shared sense of the future and of the challenges they will face in meeting it.

This will pay enormous dividends as events unfold, as change accelerates, and as stresses and challenges accumulate, because a foundation of shared understanding will enable them to communicate with one another more effectively about what they discover, and will thus accelerate their ability to make good decisions and shift quickly to implementation.

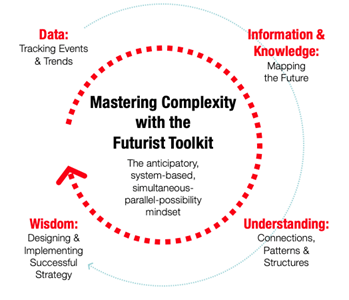

Conclusion: From Reaction to Anticipation

The overall logic I am describing here began with the data, compiled from a great many sources to provide us with a robust picture of the factors shaping the present and future. We used it to create knowledge, that is, to anticipate where things may be headed, using tools like future timelines and technology roadmaps. We then transformed that knowledge into a deeper understanding through

scenario planning and strategic roadmapping.

And then, throughout the process of implementing strategy, which is the ongoing and never-ending requirement, we adjust, fine tune, adapt, and aspire to optimize. The first time we do this it maybe appear to be a somewhat linear process that we follow step by step, but once completed, it becomes a constantly iterative mode of working, a continuously looping way of thinking-doing-managing-learning.

In this way we have achieved a meaningful change in the way we operate, and by doing so we also may have achieved a significant transformation … from a reactive, event-based, linear-sequential-predictive mindset, to an anticipatory, system-based, simultaneous-parallel-possibility mindset.

We are now much better prepared to meet the requirements of the still-accelerating future.

•••

More Tools to Achieve Innovation Mastery

And speaking of boost, do you need to boost your capacity in innovation? Our Innovation Mastery program continues to attract people from around the world with 25 hours of outstanding content that has been licensed by numerous corporations to help their staff and innovation teams increase their depth of knowledge and proficiency.

Sign up for the ridiculously low price of $249 per person, with quantity discounts available – it’s a timely and super effective investment in creating a healthy future for your organization. You can check it out at www.mastery.innovationlabs.com.

The Innovation Mastery Library

With the addition of Bryan’s excellent book, the Innovation Mastery Library now consists of 16 volumes, which makes it possibly the most complete collection of books on innovation available anywhere. Check these titles out … they’re all available on Amazon.

As always, thanks for reading, please pass this newsletter along to others, and please share your comments and feedback with us!

•••

About InnovationLabs

InnovationLabs is recognized worldwide as one of the most helpful and important innovation consulting firms. We help our clients achieve world-class innovation prowess by designing innovation systems and tools, implementing innovation programs and departments, and providing fun and enlightening innovation trainings. If it’s got anything to do with innovation, we’re your key resource.

•••

Click here to download our brochure on InnovationLabs

•••

Langdon Morris is Senior Partner of InnovationLabs, one of the world’s leading consulting firms working in the areas of strategy and innovation. He is author or coauthor of more than ten books on innovation. To learn more please visit www.innovationlabs.com/

This book is about important interventions, integrations, and innovations, and about how to conceive, design and implement them

in a meaningful way for a new or existing city. It offers a Transformation Roadmap for cities, providing multifaceted pathways to overcome the Climate Emergency by attaining Net Zero.

This book is about important interventions, integrations, and innovations, and about how to conceive, design and implement them

in a meaningful way for a new or existing city. It offers a Transformation Roadmap for cities, providing multifaceted pathways to overcome the Climate Emergency by attaining Net Zero.

Continue the conversation!

Find us on these social networking sites: